Home › Market News › Stocks vs. Futures: A Guide for Retail Traders

Most of us start our trading journey with stocks. It’s the most obvious choice because it’s the only financial product that most of the general population understands. Our parents might have owned shares, we learned about stocks in our high school economics class, and we’re familiar with many of the largest companies in the stock market like Apple, Google, and ExxonMobil.

Of those traders who stick it out long enough to learn about other products, such as futures, many end up making a move away from stocks.

If you’re considering moving from stocks to futures, it’s worth understanding the differences between the two products so you can practically make the transition without surprises or regrets.

A good place to start this conversation is with the differences in cost and buying power provided by each asset class.

The leverage offered by major futures contracts is multiples of that provided to retail stock traders.

The standard retail broker offers stock traders 4:1 leverage intraday and 2:1 leverage overnight. To contrast with futures, an E-mini S&P 500 futures contract offers roughly 32:1 leverage.

The most liquid futures contract in the world—the S&P 500 E-mini—is worth 50 times the S&P 500 index value. At the time of writing, the value of the S&P 500 is $3091. Therefore, the nominal price of a single E-mini S&P future equals:

$3,091 x 50 = $154,550

The margin requirements to day trade S&P 500 futures are generally between 10% and 15%. Interactive Brokers, a favored broker for futures trading, requires just $4,743.50 of margin for intraday trading, which translates roughly to the 32:1 leverage figure mentioned earlier.

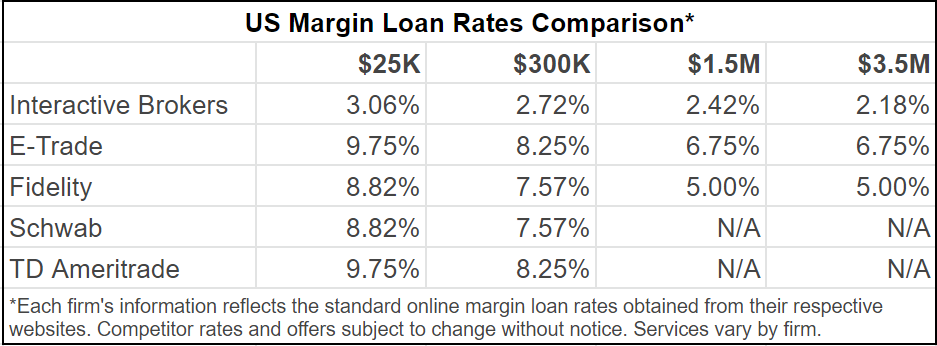

Aside from the low levels of leverage offered on stocks, the margin rates are much higher than those of futures. Here’s a table from the Interactive Brokers website:

As opposed to market consolidation in the futures market, the concept of market fragmentation in the stock market is one of the key drivers behind the differences between these two asset classes. This concept becomes apparent when you look at the differences in costs between futures and equities data feeds.

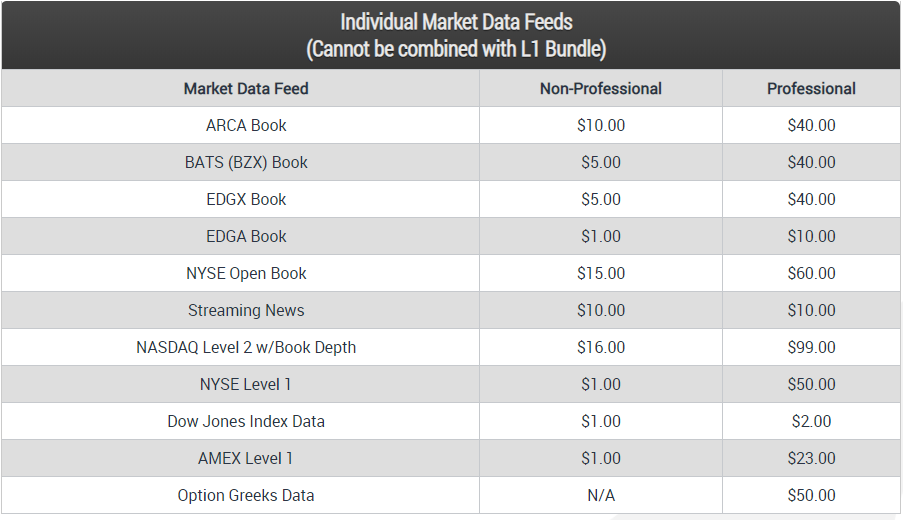

There are only four major futures exchanges in the U.S. market, compared to dozens of exchanges, ECNs (electronic communication networks), and dark pools available for equities. Here’s a table from Lightspeed Trading, which lays out the equities data feeds they sell:

Remember, data feed brokers designate prop traders as professionals. Sometimes life is just unfair like that.

When it comes to paying for data feeds, futures traders benefit from the fact that there are only four major futures exchanges as opposed to dozens of stock exchanges, all of which have expensive data feeds to sell you.

Equities and futures have slightly different commission structures depending on which broker you use.

We recently saw the major discount brokers move to a commission-free trading model for equities. The caveat is that the trade is only free if it’s sold to a third-party market maker like Citadel. Traders who require direct market access haven’t seen their fees reduced.

The most popular futures contracts are worth tens of thousands of dollars per contract, making a per-contract pricing model much more favorable than the stock market’s per-share pricing model.

Two popular brokers for active traders – Interactive Brokers and Lightspeed Trading – charge about $2.00 and $1.29 per futures contract, respectively.

Trading low-priced stocks with direct access brokers can get quite expensive due to per-share pricing.

For instance, here’s a table showing one side of commissions on a $10,000 position in stocks of different prices at a commission rate of $0.004 per share.

The Pattern Day Trader rules dictate that stock traders with less than $25K in equity in their accounts cannot make more than three intraday trades within a rolling five day period. This rule doesn’t apply to the futures markets, making the barrier to entry lower for day trading futures than stocks. As long as you meet the margin requirements, you can trade day trade futures with any account size.

Of course, few profitable futures traders would recommend that you begin trading futures with less than $25K, to begin with, but at least there are no artificial constraints on you.

Stock and futures trades are taxed differently, with futures taxed at a much more favorable rate.

Futures contracts are considered a 1256 contract by the IRS, which are known as “60/40 contracts,” which means that regardless of the holding period of your trade, 60% of the profits are taxed at the long-term capital gains rate and 40% at the short-term capital gains rate.

The long-term capital gains rate is up to 20%, while the short-term capital gains rate is up to 37%.

Beyond the tax rate, filing futures trading profits with the IRS is infinitely easier than filing stock market profits. The IRS doesn’t require you to track additional trades, calculate cost basis, or account for wash sales.

Futures are derivative contracts, meaning there’s no theoretical limit on how many can be written by any number of parties.

On the other hand, stocks have a finite amount of shares available for public trading known as the “float.” Sure, companies can issue new shares, but they’d be diluting their shareholders, something quality companies do their best to avoid.

Futures are derivatives, meaning that they derive value from the underlying asset. Futures have value because of the contractual obligation to buy or sell an asset at a specified price on a specified date, not because a futures contract signifies real ownership of that asset. There’s no theoretical limit to how many futures contracts can be issued.

Stocks represent fractional ownership of a company. The company itself issues them, and corporate governance dictates the issuing guidelines. There’s a theoretical limit to how many shares of a company can exist at a given price.

The stock market is full of uninformed buyers and sellers who aren’t trying to predict the market’s short-term fluctuations. On the other hand, there are very few futures market casuals as they quickly blow out their accounts. The futures market is populated by the smartest, most capitalized, and informed traders in the world.

Stock trading wins out when it comes to how informed your average counterparty is, especially when trading small caps, which are dominated by uninformed retail investors buying based on a stock tip in a newsletter.

The futures markets are consolidated. Liquidity and volume are concentrated in just a few exchanges, and most futures contracts trade on only one of them. While this difference is subtle, it means that the structure of the futures market is more straightforward and tougher to exploit.

Two Major Futures Exchanges:

The stock market is more fragmented than the futures market. Liquidity and volume are spread across several trading venues, with many of those venues (like dark pools) being closed off to retail traders.

Trading Venues:

The maker-taker fees and rebates that exist in the stock market are not present in futures markets. These rebates/fees heavily influence how stocks move in the short-term.

Due to competition between stock exchanges, an incentive structure called the maker/taker model emerged. Exchanges typically pay rebates to market makers (those who provide liquidity to the market) and charge market takers fees(those who take liquidity from the market).

Critics of this business model opine that rebates have incentivized high-frequency scalping strategies that increase the market’s level of noise. On the other hand, proponents indicate that the absence of rebates would require market makers to widen their spreads.

Most futures contracts have pretty large ticks relative to stocks, most of which have penny-wide spreads.

/ES, for example, has $0.25 ticks, which works out to be $12.50 per tick. If we pretend that /ES traded like a stock, with $0.01 spreads, it will work out to be $0.50 per tick.

It’s much more expensive to pay the spread in futures markets, requiring you to think more about your order execution. If you’re deploying a short-term strategy that targets just a few ticks per trade, it virtually forces you not to pay the spread.

The U.S. stock market is open for just 6.5 hours, with an insignificant amount of volume outside the regular market session. Futures markets are open nearly 24 hours a day on trading days.

As the trading became electronic, many expected stock markets to trade 24 hours a day as well, but so far, there just isn’t demand. Stock markets are local, people tend to want to buy stocks from their home countries, so there wouldn’t be enough volume to make it worth it for stock exchanges to keep markets open 24 hours.

Commodities, on the other hand, are global. People in China need to hedge their crude oil exposure as much as those in the United States. Because of this, there are several regional sessions throughout a day in the futures market between the start and end of U.S., European, and Asian business hours.

These additional sessions can be a gift and a curse for futures traders. On the one hand, if you’re a profitable trader, it allows you to trade more with your positive expectancy, which will dramatically increase your returns over a long time frame. On the other hand, many traders are overwhelmed by all of the opportunities available and stretch themselves too thin, often depriving themselves of sleep to trade, leading to sub-optimal results.

In the stock market, short sellers have a structural disadvantage because stocks have a finite float, requiring you to borrow shares to sell short.

When borrowing shares, you have to pay an interest rate to the party you’re borrowing from, and sometimes you have to pay “locate” fees to your broker to track down shares for you to borrow. The party you borrow shares from can call your shares due at any time, forcing you to repurchase them in the open market at the current price.

When you “short sell” a futures contract, you’re not short selling at all. You’re buying a contract that obligates you to sell that commodity at a given price in the future. No borrowing or locating is necessary, making the futures market a more level playing field between bulls and bears.

Over the ten years ending in 2013, 55 stocks within the S&P 500 index lost more than half of their value.

When allocating capital to an individual company, you’re exposing yourself to the market, sector, and commodity risks, and that the management won’t disregard shareholder value, commit accounting fraud, and a variety of other unquantifiable risks.

The S&P 500 has lost 10% of its value just three times in its history. There are dozens of stocks gapping up and down every day.

Take the story of a retail short seller who took a short position on a small-cap biotech stock that gapped up overnight after “Pharma Bro” Martin Shkreli announced his intentions to buy the company.

One futures contract is a large position. Unfortunately, you can’t buy 1.3 crude oil futures, even if that’s what the optimal position size would be for you. With their low per-share pricing, stocks make it simple to buy or sell the optimal amount based on your models.

Ultimately, the choice is up to your individual trading preferences. Both asset classes offer the possibility of huge profits, but also the not-insignificant possibility of losing your shirt. Responsibility and discipline are key to success regardless of what you’re trading.

If you’re interested in learning more about trading futures, be sure to check out our series on the 5 Ways to Stop Gifting Money to the Markets and our Beginner’s Guide to Trading Crude Oil Futures.